The Psychology of Music: Intensity

In this second and following three essays, we will discuss the practical approaches to music arrangement using a psychological approach. These include the following elements:

-Intensity

-Transitions

-Transformations

-Improvisation

These four elements begin to get us thinking about arrangements using a psychological mindset, so that our music aims at affecting audiences in the most powerful way. First, we will address the reasons why we would want to do this. It is not to manipulate or control, but as discussed in part 1, it is to satisfy the basic desire of human beings who go out to see and experience music: the desire to transform. What do we mean by this?

People go out to see gigs and party to get out of their normal states of mind, to experience themselves in a new way, and to forget about the day-to-day problems and issues. In this way, we as creators provide a critical service which is often undervalued and misinterpreted by society. We provide people, not just an escape, but an experience of another identity. When people hear music and lose themselves, feeling a sense of wonder and oneness with the people around them, they are experiencing the awe and nature of existence, they are attuned to the present moment and give up aspects of everyday identity, or ego. When they allow themselves to give up their everyday ego self (persona) to the music, they get to glimpse of other aspects of their being.

At the most basic level, this provides relief and temporary joy which leaves them refreshed and ready to resume the world again. But at its most intense, this experience can be a profound spiritual experience that never leaves them, reminding them of who they are capable of becoming, and leads them to search for the higher things in life. This may happen when one suddenly feels a profound sense of oneness with everything around them during a heightened musical experience. They may become exalted and feel a deep connection with everything around them. This fleeting experience has the power to transform one’s identity permanently, and alter the course of their lives in trying to understand the experience or seek it anew. This leads many people to develop a spiritual practice, seek god or a higher self, or simply to grow in the appreciation for music and the arts.

These intense experiences are transformative.

When we think of music from a psychological perspective, we are expanding our skill set to help people achieve more meaningful experiences, to connect more strongly. This is an important service, perhaps even a divine calling, for artists are providing a service to humanity by facilitating their transformation, satiating their desire to feel themselves anew, and we mustn’t downplay the impact that this can have for individuals and collectives.

Ritual cultures knew this perfectly and had a precise system in place for evoking these states. Their music practices were defined and refined over generations, and passed down to the next iteration of musicians eager to serve their community. In exchange, these musicians were revered for their mastery of the art and service to the community, and were treated with respect, awe, and thanks, for their ability to turn everyday events into transformative experiences.

The music in these ritual cultures followed defined rules and traditions which were intricately linked to psychological processes, but this did not mean it remained static and stuck in time, for these traditions understood that part of the process of connection is evolution with the times, and thus used improvisation and musical evolution as a core aspect of the musical system and integral to its effects. The main difference between these cultures and Western culture, is that they provided a spiritual container for the effects of transcendence, often due to some deity or god. When people underwent states of rapture and transformed, the culture had in place a rich belief system that let them experience themselves as an expression of a cultural deity, a supernatural force that had manifested on earth to express itself through the human. Devotees could understand this metaphysical phenomenon through a cultural lens, and use the experience as a form of praise and worship that reenforced their beliefs and social bonds.

In the West, we have grown cynical of our previous gods and deities, and so our mystical transformations no longer have a cultural and spiritual support. Instead, Westerners flee to the Amazonian shamans or Indian gurus looking for spiritual support, or create their own cults often with varying results. While the majority face their desires for transcendent experiences on their own, often feeling lost as they seek answers to their deep experiences, or seek them out through drugs, alcohol, or thrill-seeking activities. Electronic music festivals and clubs provide an important space for many of these ritual experiences that have been lost due to the degradation of religious rituals in Western culture. They provide the emotional stimulation necessary for transcendent experiences, alongside the multi-sensory contexts that enables sensory overload as it does in many religious rituals. All these elements contribute to the totality of intensity: musical, bodily, psychologically, and collectively to enable altered states. Music is a core feature of these events that uses intensity to contribute to its heightened experiences.

Intensity

To think about music from a psychological perspective, we must use terms that describe its impact of human perception. To do this, we cannot rely on general music terms, such as chords and harmony, for we must change our thinking to consider music as a relational experience that involves both artist and audience. In this type of thinking, music only exists when it is experienced, not as an isolated series of chords and rhythms. Thus, we must approach music from the way it impacts other humans. Intensity is one term we can use for this purpose, which is universal and helps us understand how music impacts a listener. When music is high or low intensity, it suggests a feeling, and emotional state, and communication between the musician and audience, and thus, it is a communal language. It describes how music is an exchange between a creator, sonic output, and its reception.

Intensity can include chords, harmony, rhythm, and melody, but it is not intricately defined by it. Musical intensity includes different cultural instruments and styles, approaches and sonic elements, and thus, intensity is a cross-cultural experience, meaning it is not dependant on the specific cultural style and allows variation. If we focus on intensity in music, then it doesn’t so much matter how the tools we choose to express our music, but what becomes important, is how we choose to create intensity. It gives us a psychological language which is universal, communal, and supports musical variation and evolution. This does not mean that there aren’t cultural differences and variations, but simply enables us a language to think about music as a psychological and collective experience.

In music that seeks transcendent experiences, such as ritual music or certain forms of electronica, intensity has a specific pattern that can be mapped. Ernst Kurth (1934/2022) tells us that intensity manifests as waves which affect the psyche, and are interpreted intuitively by the subject. The trajectories of intensity build towards high points, which is the accumulation of energy, as in the following quote:

“There is a continued effect of individual high points that is unique to musical forms of motion- a result of the conscious or unconscious will. In this way, we may sense not only the continual transformation of potential to kinetic energy over a series of arches but also an accumulation of energy that reaches a global high point” (Kurth 1934/2022)

Kurth suggests that musical energy moves in waves, and these movements are deeply connected to our psychological nature: we are tuned to feel them and respond to them subjectively. The masterful musician learns to understand these developments and plays with them to move his audience. Kurth also suggests that the kinetic force of intensity reaches a maximum high point, which is sequential and linked through successive waves. The sequential waves enable musical intensity to move in trajectories of high and low troughs which are felt intuitively and subjectively but musician and audience.

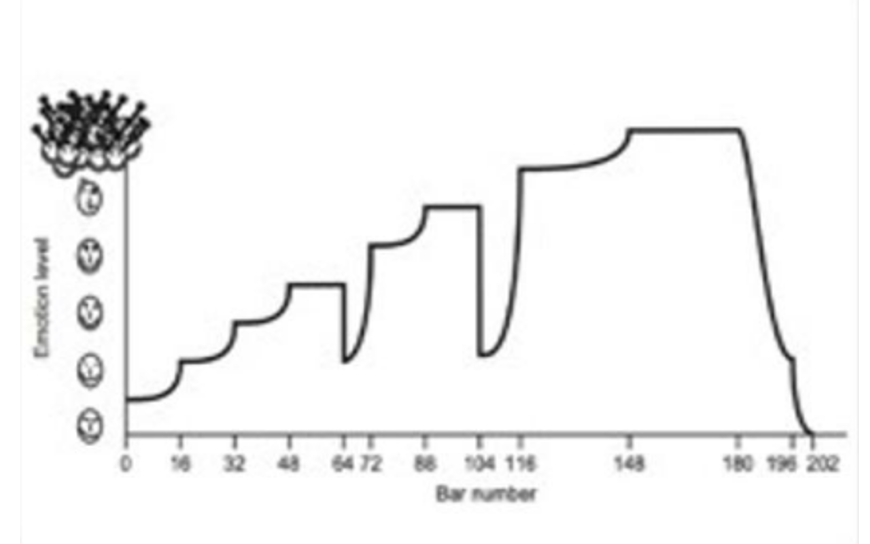

The wave development of energy in electronic dance music appears in a diagram by Rick Snowman (2009), who shows the relationship between EDM musical form and emotional exhilaration in audience.

Rick Snowman, 2009, Taken from Solberg 2014 p.67, shows typical EDM track development and its relationship to emotional intensity in audience.

The diagram shows that EDM music exhibits waves of intensity that reach a global high point, and are linked sequentially, so that one wave is followed by another greater wave and peak. The effects of electronic music often produce transcendent experiences, as shown by Sylvan (2009), who researched subjects at electronic music raves and suggested correspondence with experiences with West African possession rituals.

“There are also strong continuities with some of the features of West African possession religion. Because of the high amplification and pounding insistence of house music beats, which are felt in the body as much as they are heard by the ears, the groove is often compelling to the point of trance induction for the dancers... When a large group of dancers enter this state together, it often results in what DJs and dancers refer to as ‘peaks’, palpable energy surges on the dance floor... Such peaks are one of the main goals of the house music dance club experience and are sought after by DJs and dancers alike. There can be several peaks in the course of an evening of music and dance, each with its own distinct characteristic energy (Sylvan 2009, 127-128).”

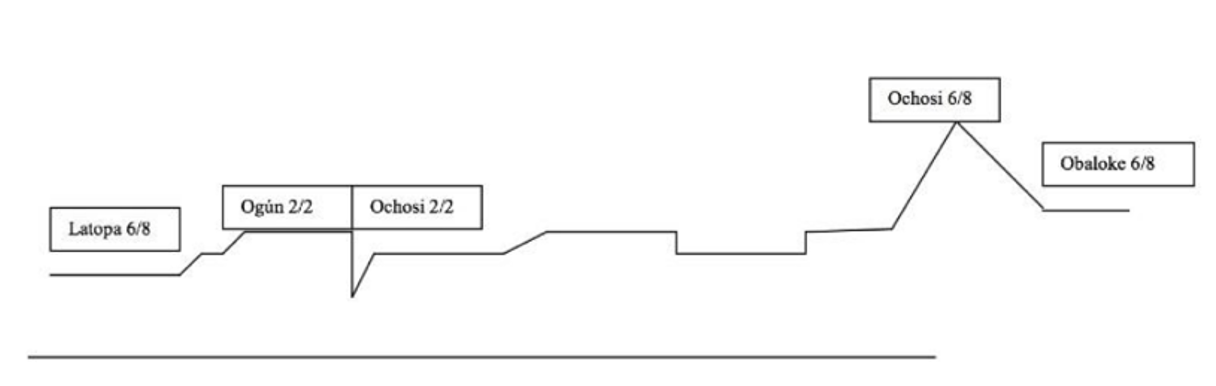

Afro-Cuban ritual music exhibits similar wave arcs of intensity, with trajectories of intensity controlled by increasing tempo from 87 bpm to high levels of up to 140 bpm. These intensities rise to a maximum point which are associated with the onset of spiritual possession, and are distributed sequentially through a succession of rhythms (toques).

Line shows the rise and fall of tempo adjustments across five rhythms (toques) in Afro-Cuban Oro Seco music. (Diaz 2019, p.142).

J.H. Kwabena Nketia (1988, p.54, 85) suggested that intensity is a core feature in many styles of African music linked to the actions of the ritual priest and his desire to manifest their deities. In fact, in central African music there is a devotee specifically assigned to ensuring intensity is high by beating a stick to signal to the musicians if energy is waning.

In some cultures, like the Wagogo peoples of central Tanzania, intensity is used as anaesthetic, used at the moment of a boys circumcision ritual to ease the pain (Vallejo 2007, p.12). At the moment the cut is about to be made, the boy is encircled by the tribe, and they all sing polyphonically to overwhelm the boy’s senses. It is believed that this overload lessens the pain of the cut.

A similar method is used in afro-Cuban rituals when it is believed a devotee is about to become possessed. At this point, the musicians direct their sonic energy towards the dancing subject, singing and playing more intensely and often ringing an achere bell close to the devotees ear (Navarro 2013, p.45). This sensory overload is believed to encourage the arrival of the spirit which pushes the devotee into a transformed state.

These examples show how high intensity is associated with transcendent experiences in various cultures. In electronica it is the point of drop, the musical high point that evokes a sense of the spiritual, and in ritual cultures, intensity is associated with sensory overload leading to possession or the abasement of pain.

The connection between intensity and heightened experience highlights the cross-cultural application of these musical devices. Intensity may be created using drums and chants in an African society, or using electronic technologies in a club context, and the interpretation of its effects may be vastly different between cultural groups. But the universality of intensity as a psychological phenomenon occurs because humans are attuned to feeling tension in their bodies, and thus, is a critical part of the performance of music.

Intensity ranges from very low to high peaks, overloading the audience due to a variety of factors, which include its high volume, wide frequency range, rhythmic complexity, rhythmic divisions, repetition, cycles ranges, pitch, density, tempo variations, embellishments, call and response, register shifts, rhythmic contrasts, use of noise instruments, and other methods that cultures use to develop intensity. An understanding of intensity offers musicians a method to connect directly with the psychological apparatus in humans, Increasing the likelihood of creating peak experiences in their audiences.

In the next essay, we look at how abrupt transitions empower music, enabling us to create impacts that have psychological effect.

Thanks for reading. If you want more information about these topics then head over to https://www.vincentsebastian.com/shop for various free and paid resources, such as artist production, DAW templates, or books. Don’t forget to join the newsletter to receive the latest news, courses, and thought-provoking essays, Also, you can check out my music here.