The Psychology of Musical Transformation.

“Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.”

William James (1902) The varieties of religious experience

In the last episode, I talked about transitions, and the way we use transitions to enhance our music arranging. Transitions are symbolic musical objects that signal our transition into new states of consciousness. When achieved masterfully and in the right context, a well-timed transition can push audiences into new zones of experience. We discussed how these transition symbols appear in traditional rituals, both in the ritual spatial design as well as the multiplicity of symbol objects and actions that serve to drive an initiate into the liminal space. The liminal, as described by Turner, is the in-between space, when one’s previous identity has been dissolved but a new one has not yet emerged. This leads us perfectly to the next topic of our discussion about the psychology of music arranging, which is transformation.

Transformation is the outcome of music arranging that seeks to provoke altered states in it’s audience. Rather than feel different emotions, such as sadness, or joy, or anger, the art of transformation seeks to create the experience of a new experience of identity and reality: a total shift in consciousness. We do this by approaching music as a symbol of consciousness. Like water that turns from liquid to steam through intensification of heat energy, we use musical intensity to foster a transition into a new state of consciousness.

From the perspective of musical arrangements, there are two core systems by which we create a musical transformation, either using a through-composed or partially through-composed form. I will explain both next.

Partially through-composed form

This form is common in electronic dance music which features a main groove, leading to a distinct middle section which culminates in a drop, before introducing a variation to the original groove. For a partial transformation to occur, the new groove must contain elements of the old, but also introduce new elements (i.e. novelty). It is the combination of repetition and novelty which ensures a transformation in a partially through-composed form. Margaret Drewal, in her study of African Yoruba culture, found that this type of approach was commonly found in community festivals that lasted over many days. Dancers would take traditional costumes and gradually alter them in novel ways, adding new elements, cutting them up, or wearing them in unorthodox styles to show innovation as the festival progressed. By the end of the festival, the outfits, movements, and aesthetics had transformed into new variations of the previous, creating innovation and evolution that mixed tradition with modernity. A partially through-composed form could include a similar rhythm combined with a shift in texture, riff, chord progression, instrumentation and introduction of a new melody, as appears in my own music with Oyobi in the song ‘Transcendence’.

Many other styles of music may use this form as well. Classical music may take a theme and alter it so that a new variation appears by the end of the piece. What is important to note, is that the process of transformation of consciousness, as is being discussed here, necessitates a combination of all previous musical devices to be effective- this includes the masterful use of intensity, impactful transitions, improvisation (which will be discussed in the following episode), and a transformation. Thus, any element on its own is not sufficient, this is an art and a holistic practice based on ritual: which is the combination of a multi-sensory systems of elements to create psychological effect.

Figure 1.1: Partially through-composed form

Through-composed form

Through composed form is used frequently in afro-Cuban liturgical music and in some rock music (such as Queens Bohemian Rhapsody). It involves the total transformation of the music by the end of the composition. A song may start using one type of rhythm and melody, and through the masterful use of intensity and transitions, arrive at a final transformation that contains a new type of music. This includes a drastic change such as alterations to rhythm, tempo, time signature, key signature, instrumentation, density, chant/melody, period length, and others. By the end of the composition, the song has drastically transformed across multiple music domains. In afro-Cuban liturgical music this includes a shift in tempo of up to 40 Bpm, a change of chant and period length, shifts in rhythms, time signature, and a drastic increase in intensity.

Figure 1.2: Through-composed form

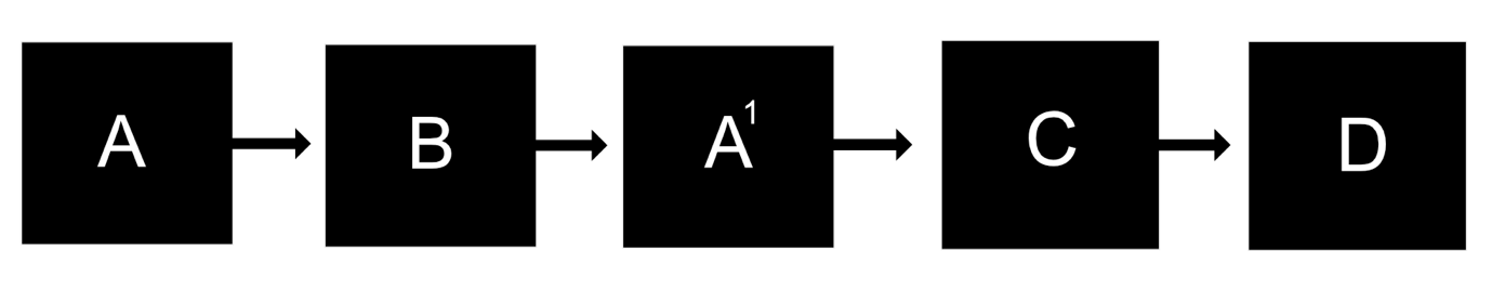

Combinations of partial and through-composed form

We may also mix these two forms to create longer structures that create a gradual transformation. A combined method may begin with a partial through-composed form, and then instigate a more drastic transformation. This type of form could have a partial culmination at (A1), and then continue the transformation into a new zones of (C) and (D). These types of transformations are used in liturgical rituals or electronic music sessions where music is played continuously for hours, enabling longer sequences to be achieved over a longer period of time. This has a profound effect of entraining audiences over the course of various ceremonial processes, and used to create sequences of journeys that fluctuate in intensity, tempo, and chant.

Figure 1.3: Combined through-composed forms

The Psychology of Musical Transformation

All of these transformations establish a development away from an initial musical idea, and don’t resolve the composition by returning to the main melody or hook. Instead, they create the feeling of change, development, evolution, and the sense of no-return. This type of form is akin to real life, because, while we may feel we have returned to a familiar house, place, or state, this is but an illusion, because things are continually changing. We can never fully recapture an old state and we are always being renewed. The through-composed form captures this fact, leaving behind the sense of resolution and instead propelling us into a new zone. It replicates the innate state of nature, and thus, it is more aligned with our experience of reality.

It does not try to ‘bring us back’ to a previous state, but instead aims to take us on a journey to a new vista to experience ourselves in a new way. When we participate in this type of music, the music acts as a symbol that asks us to contemplate, participate, and to integrate its meanings within us. Thus, we are taken by the music through a journey which is embedded within the musical form. Through-composed music leads to a transformation, and by being taken by the music, we also arrive at a new place, a new state, that symbolically depicts the space which the music wants us to go. Ritual music, such as that used in liturgies, or electronic festivals and raves, uses these techniques to create altered states in its audiences, providing new experiences of reality, personality and community, that can haver permanent life-altering effects.

In the next article, we discuss improvisation, which is the glue that holds these three elements – intensity, transition, and transformation- together. This is not the typical view of improvisation that you may have heard before, but a different way of thinking about improvisation, not as a type of ‘free creativity’ but as a type of ‘profound intuitive receptivity’.

Thanks for reading. If you would like to read previous related articles about Music Psychology then head to https://www.vincentsebastian.com/blog. At the site, you can also find resources for creating your own music, and various free and paid resources for artist production, DAW templates, or books. Also, you can check out my music here.

References

Drewal, M.T., 1992. Yoruba Ritual: performers, play, agency. Indiana University Press.

Oyobi, www.oyobi.com.au

Turner, V., Abrahams, R. and Harris, A., 2017. The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Routledge.1966